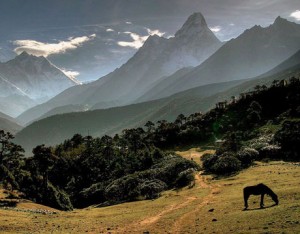

A Sanskrit proverb holds that “A hundred divine epochs would not suffice to describe all the marvels of the Himalaya” — so long to describe, how much longer to understand. Modern scintific of Himalayan ecology has butchered a tiny tip of the knowledge to be learnt. But even :hat tip inexorably leads to the grimmest conclusions . Man’s onslaught has rendered the Himalaya amongst the most endangered environments in the world. In the subcontinent, the Himalaya rank as the region most in need of 11 conservation, both because of the deterioration in environment and in view of our relative ignorance of the bi

ignorance of the bi![]() ology and ecology of high-altitude communities. Slowly, this begins to change but the task is immense. The Himalaya contain more endangered species of mammal than any other area of India and are remarkable in possessing almost one third of the world’s mammalian species that could be called true mountain animals. M.K. Ranjitsinh has noted that “the outlook for wildlife in most parts of the Himalaya is grim, in some places even desperate,” and G.B. Schaller warned that just as we are I becoming more aware of the splendor of past and present wildlife of the Himalaya we are denying it a future. He describes mountains without wildlife as “stones of silence,” an evocative and thoughtprovoking phrase.

ology and ecology of high-altitude communities. Slowly, this begins to change but the task is immense. The Himalaya contain more endangered species of mammal than any other area of India and are remarkable in possessing almost one third of the world’s mammalian species that could be called true mountain animals. M.K. Ranjitsinh has noted that “the outlook for wildlife in most parts of the Himalaya is grim, in some places even desperate,” and G.B. Schaller warned that just as we are I becoming more aware of the splendor of past and present wildlife of the Himalaya we are denying it a future. He describes mountains without wildlife as “stones of silence,” an evocative and thoughtprovoking phrase.

Rich Variety: What would we be losing? The youngest, largest and highest chain of mountains in the world, the Himalayan range must lay claim to being one of the most fascinating and spectacular natural wonders of our earth. To speak of the Himalaya may give a false impression of biological homogeneity when in fact it covers a wide and varied mosaic of different biotypes — east-west, north-south and altitudinally. Geologically divided into the three regions of tr ans- Himalaya, middle Himalaya, and outer Himalaya and Siwaliks, the vegetation ranges from lush subtropical forests of the foothills to the bitterly cold high-altitude deserts of Ladakh and the Tibetan plateau. Thrown up 60-70 million years ago with activity still continuing, the Himalaya have acted both as a bridge and a barrier. The asymmetrical collision of the continental plates resulted in an inflow of oriental fauna through the northeast before the Afro- Mediterranean elements which followed through the northwest. The present flora and fauna spcies of the east and west regions reflect this —the former showing a close relationship with the western-Chinese pattern and the latter having Euro-Mediterranean affinities. Besides these, many species have evolved from the previously present Central Asian or palaearctic fauna and given rise to high endemism with strong generic links to Tibet and Central Asia.

ans- Himalaya, middle Himalaya, and outer Himalaya and Siwaliks, the vegetation ranges from lush subtropical forests of the foothills to the bitterly cold high-altitude deserts of Ladakh and the Tibetan plateau. Thrown up 60-70 million years ago with activity still continuing, the Himalaya have acted both as a bridge and a barrier. The asymmetrical collision of the continental plates resulted in an inflow of oriental fauna through the northeast before the Afro- Mediterranean elements which followed through the northwest. The present flora and fauna spcies of the east and west regions reflect this —the former showing a close relationship with the western-Chinese pattern and the latter having Euro-Mediterranean affinities. Besides these, many species have evolved from the previously present Central Asian or palaearctic fauna and given rise to high endemism with strong generic links to Tibet and Central Asia.

Elusive Cat: No animal better epitomizes the character and concerns of the mountain environment than the snow leopard (Panihera uncial ), that beautiful and elusive cat of the high altitudes of Central Asia. A survivor of the icy rigors of the Pleistocene era, its range is immense, covering the entire Himalaya between altitudes as low as 6000 feet (1850 meters) in winter to 18,0 00 feet (5550 meters) in summer. Being a shy inhabitant of remote habitats, it has seldom been seen by any but those humans sharing its mountainous home. Only recently have some facts emerged about the ecology of this high-altitude predator.Somewhat smaller than the leopard ( Panthera pardus), but with a relatively longer tail, the snow leopard has a thick and beautiful spotted coat of soft gray, paling to pure white on the underside. This has certainly contributed to its rarity, for although strictly protected, many still fall to poachers’ bullets and traps, for in the world of fashion there remain those ignorant and rich enough to make taking such risks worthwhile. The snow leopard uses large areas in order to obtain enough sustenance. In winter months, it sometimes ventures near villages to lift domestic livestock, but its main prey are the wild sheep and goats that share with it these stark and snowy wastes.

00 feet (5550 meters) in summer. Being a shy inhabitant of remote habitats, it has seldom been seen by any but those humans sharing its mountainous home. Only recently have some facts emerged about the ecology of this high-altitude predator.Somewhat smaller than the leopard ( Panthera pardus), but with a relatively longer tail, the snow leopard has a thick and beautiful spotted coat of soft gray, paling to pure white on the underside. This has certainly contributed to its rarity, for although strictly protected, many still fall to poachers’ bullets and traps, for in the world of fashion there remain those ignorant and rich enough to make taking such risks worthwhile. The snow leopard uses large areas in order to obtain enough sustenance. In winter months, it sometimes ventures near villages to lift domestic livestock, but its main prey are the wild sheep and goats that share with it these stark and snowy wastes.

Mountain Sheep: The Himalaya contain more species of sheep than any other mountain range. Pride of place must go to the Marco Polo sheep ( Ovis Gammon polii), whose ratio of horn-length to body-weight exceeds that of any animal in the world. These horns form open graceful spirals with the tips arcing up, out and then down again. A northern subspecies of the argali ( Ovis ammon), Marco Polo sheep may still be fairly common in the Russian Pamirs and Wakhan corridor of Afghanistan, but within the subcontinent it is a rare animal existing only in northern Hunza where its magnificent head has long attracted hunters. In its spartan, near-desert landscape home, particularly severe winters also take their toll of this grand creature.

the world. These horns form open graceful spirals with the tips arcing up, out and then down again. A northern subspecies of the argali ( Ovis ammon), Marco Polo sheep may still be fairly common in the Russian Pamirs and Wakhan corridor of Afghanistan, but within the subcontinent it is a rare animal existing only in northern Hunza where its magnificent head has long attracted hunters. In its spartan, near-desert landscape home, particularly severe winters also take their toll of this grand creature.

Another race of the argali is the nayan or great Tibet an sheep ( Ovis amnion hodgsoni). This is the largest of all wild sheep. Long in the leg and graceful, it inhabits the trans-Himalaya plateau, an area of desolate plains and low undulating hills, experiencing extreme temperatures, from scorching summers to freezing winters. Nayan are migratory, wandering wherever food and water may be found, and are natural prey of the Tibetan wolf which is the chief predator of the trans-Himalayan uplands and plateaus.The urial or shapu ( Ovis orientalis) is the smallest of the wild sheep and is distributed through the western Himalaya where several different races are distinguished.

an sheep ( Ovis amnion hodgsoni). This is the largest of all wild sheep. Long in the leg and graceful, it inhabits the trans-Himalaya plateau, an area of desolate plains and low undulating hills, experiencing extreme temperatures, from scorching summers to freezing winters. Nayan are migratory, wandering wherever food and water may be found, and are natural prey of the Tibetan wolf which is the chief predator of the trans-Himalayan uplands and plateaus.The urial or shapu ( Ovis orientalis) is the smallest of the wild sheep and is distributed through the western Himalaya where several different races are distinguished.

While horn shapes and colors differ, the adult rams all wear a great ruff growing from either side of the chin and extending down the throat. Adapted to differing environments, from the barren stony ranges of Sind and Baluchistan to steep grass hillslopes in Ladakh, this progenitor of domestic sheep has also attracted hunters’ bullets and many populations have been decimated to rarity.

Another Himalayan mammal, originally classified as a sheep, is the bharal (Pseudois nayaur). Its physical characteristics are so intermediate between sheep and goats that taxonomists have had trouble classifying it. Exp ressing thoughts on their evolution in his book, Mountain Monarchs, G.B. Schaller writes that “in general the behavioural evidence confirms the morphological evidence that bharal are basically goats. Many of the sheep-like traits of the bharal can be ascribed to convergent evolution, the results of the species having settled in a habitat which is usually occupied by sheep.” For bharal, like sheep, graze on open slopes, whereas goats prefer more precipitous cliff habitats. It is an animal of the Himalaya and trans-Himalaya zones and is still common in some places as far apart as Eastern Ladakh and Bhutan.

ressing thoughts on their evolution in his book, Mountain Monarchs, G.B. Schaller writes that “in general the behavioural evidence confirms the morphological evidence that bharal are basically goats. Many of the sheep-like traits of the bharal can be ascribed to convergent evolution, the results of the species having settled in a habitat which is usually occupied by sheep.” For bharal, like sheep, graze on open slopes, whereas goats prefer more precipitous cliff habitats. It is an animal of the Himalaya and trans-Himalaya zones and is still common in some places as far apart as Eastern Ladakh and Bhutan.

Mountain Goats: The Himalaya house three species of true goat — the ibex ( Capra ibex), occupying the highest altitudes; with the markhor ( Capra falconer) and wild goat (Capra Maus). inhabiting cliffs generally below 12,000 feet (3700 meters). The ibex, found in the Himalaya west of the Satluj gorge, leads a tenuous existence in spite of its adaptability, as the balance between death and malnutrition in its austere habitat is delicate indeed. The spectacular markhor found in the Fir Fanjal range and west to the Hindu Kush and Karakoram, lacks the underwool of the ibex and prefers to remain below the snow line. The markhor’s horns are uniquely spiraling whereas the wild goat has scimitar horns similar to those of the ibex.

The Himalayan tahr (Heniitragus jenilahicus s), differs from true goats in having short curved horns rather than long sweeping ones. This tahr is found throughout the Himalaya from the Fir Fanjal to Sikkim and Bhutan in several vegetation zones between 8000 feet and 15,000 feet (2500 4500 meters) though rarely going far above the tree line. A beautiful and robust creature, the male Himalayan tahr has a conspicuous coppery brown ruff and mantle of flowing hai r draping from the neck and shoulders to its knees and from its back and rump to its flanks and thighs. Serow ( Capricornis suniatraensis) and goral ( Neniorhaedus gora ), two of a group known as goat-antelopes, are also found in both western and eastern areas. The third member of this group, the takin ( Budorcas tricolor ), a large relative of the musk-ox, is found only in restricted numbers in the eastern Himalaya. Recently the Royal Government of Bhutan declared it the national animal and set up special reserves for its protection. Gregarious by nature, the takin partakes of long seasonal migrations and is at home in general as well as rhododendron forest. The movements of serow and goral in their selected habitats are very restricted. The serow, solitary and reclusive by nature, occupies small cliffs and thickly forested ‘ ravines, whereas the goral prefers grassy slopes width broken ground, usually at lower altitudes in the southern Himalaya.

r draping from the neck and shoulders to its knees and from its back and rump to its flanks and thighs. Serow ( Capricornis suniatraensis) and goral ( Neniorhaedus gora ), two of a group known as goat-antelopes, are also found in both western and eastern areas. The third member of this group, the takin ( Budorcas tricolor ), a large relative of the musk-ox, is found only in restricted numbers in the eastern Himalaya. Recently the Royal Government of Bhutan declared it the national animal and set up special reserves for its protection. Gregarious by nature, the takin partakes of long seasonal migrations and is at home in general as well as rhododendron forest. The movements of serow and goral in their selected habitats are very restricted. The serow, solitary and reclusive by nature, occupies small cliffs and thickly forested ‘ ravines, whereas the goral prefers grassy slopes width broken ground, usually at lower altitudes in the southern Himalaya.

Ruminants: Evolutionally, the earliest known ruminants are the antelope and gazelle group of the family Bovine . In the Himalaya they are represented by the Tibetan antelope or chiru (Pantholops hodgsoni ), and the Tibetan gazelle ( Proeapra pietieaunta). The chiru is another creature of the high Tibetan plateau and may also be found seasonally in northern and eastern Ladakh. With a special breathing system and the finest underwool to protect it from the extreme cold, the chiru is well adapted for the high altitude desert areas that constitute its home. Tibetan gazelle have all but disappeared in Ladakh though they may be found in Pakistan and Bhutan as well as in the Tibetan plateau.

Lett, chukor are often seen in small coveys on Aare , arid hillsides in the western Himalaya; the Himalaya tahr ranges from Pakistan to Arunachal Pradesh. Above, the kiang or Tibetan wild ass is restricted in India to a small area of La dakh Other animals which occasionally cross the main Himalayan divide in small numbers from the trans-Himalayan ranges are the wild yak (Bos grunniens) and kiang, the Tibetan wild ass ( Equus hemionus kiang). The yak is the largest animal of the mountains; massively built and heavily coated, it inhabits the coldest, wildest and most desolate areas and is one of the highestdwelling animals in the world. The kiang, whose close relative runs in the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat, is another creature of the Tibetan plateau and plains of northern Ladakh.

dakh Other animals which occasionally cross the main Himalayan divide in small numbers from the trans-Himalayan ranges are the wild yak (Bos grunniens) and kiang, the Tibetan wild ass ( Equus hemionus kiang). The yak is the largest animal of the mountains; massively built and heavily coated, it inhabits the coldest, wildest and most desolate areas and is one of the highestdwelling animals in the world. The kiang, whose close relative runs in the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat, is another creature of the Tibetan plateau and plains of northern Ladakh.

Of the other ungulates of the Himalayan region the samba and barking deer, though found at high altitudes in the southern Himalaya, are not truly mountain species. However, two species of red deer are endemic to the area and both are highly endangered. Indeed, the status of the shou — so-called Sikkim stag (cervus elapses walliehi) though it was never found in Sikkim –is so uncertain that it may well already be extinct. The position of the hangul or Kashmir stag ( Cervus elapses hanglu ), is a little better with a population of around 500 living protected in the Dachigam National Park in Kashmir.

In contrast to the restricted ranges of these red deer, the musk deer ( Moseses mosehif eras) may be found over a wide area of central and northeastern Asia. In spite of this, their status is hardly less endangered for the male carries the musk pod which, commanding exorbitant prices, has made the musk deer the chief target of every poacher in the Himalaya. Though protected by most stringent laws, unscrupulous perfume manufacturers still encourage the decimation of this deli ghtful creature. Threatened thus throughout its range, the best chances for viewing it are within preserved areas such as the Kedarnath Musk Deer Sanctuary in Uttar Pradesh and the Sagarmatha National Park in Nepal.

carries the musk pod which, commanding exorbitant prices, has made the musk deer the chief target of every poacher in the Himalaya. Though protected by most stringent laws, unscrupulous perfume manufacturers still encourage the decimation of this deli ghtful creature. Threatened thus throughout its range, the best chances for viewing it are within preserved areas such as the Kedarnath Musk Deer Sanctuary in Uttar Pradesh and the Sagarmatha National Park in Nepal.

Bears: The ungulates described here constitute the largest group of mammals in the Himalaya and many are the main prey species of the larger predators. Though the snow leopard may be the most spectacular of these, the largest carnivore of the mountain species is the brown bear ( Ursus arctos isabellinus ). Once abundant in the Himalaya, in some parts of its range the brown bear is now even more seriously threatened than the snow leopard. As an inhabitant of the lessvegetation- rich higher altitudes, the brown bear is more of a predator than its lower-living relative, the Himalayan black bear thibetanus), whse ratio of fruit to flesh is higher. But the black bear is also omnivorous and a great meat lover, eagerly scavenging carcasses as well as occasionally bringing down sick or young prey of its own. The black bear has the largest range of all the Himalayan mammals, extending over the full mountain range and into Southeast Asia. Safer from human attack than most of the large Himalayan species, it nevertheless comes into conflict with people due to its propensity for crop raiding. Being especially fond of maize, many injuries and deaths on both sides occur during the harvesting season. A third member of the bear family to be listed amongst Himalayan fauna is the Tibetan blue bear, but it is so rare that almost nothing is known of it.

). Once abundant in the Himalaya, in some parts of its range the brown bear is now even more seriously threatened than the snow leopard. As an inhabitant of the lessvegetation- rich higher altitudes, the brown bear is more of a predator than its lower-living relative, the Himalayan black bear thibetanus), whse ratio of fruit to flesh is higher. But the black bear is also omnivorous and a great meat lover, eagerly scavenging carcasses as well as occasionally bringing down sick or young prey of its own. The black bear has the largest range of all the Himalayan mammals, extending over the full mountain range and into Southeast Asia. Safer from human attack than most of the large Himalayan species, it nevertheless comes into conflict with people due to its propensity for crop raiding. Being especially fond of maize, many injuries and deaths on both sides occur during the harvesting season. A third member of the bear family to be listed amongst Himalayan fauna is the Tibetan blue bear, but it is so rare that almost nothing is known of it.

Dilettantism Dogs and Cats:latives of the bear family are the dogs. The most conspicuous representative in the Himalaya is the wolf ( Canis lupus). Feeding on hares and marmots as well as the larger goats and sheep, the wolf is an animal of the western region and may be found in Ladakh, where it is still relatively common. Another member of this family is the wild dog ( Cuon alpinus), which can be found in the Himalaya and trans-Himalaya, but its rarity in the more accessible areas makes its  status uncertain and little information concerning it is available. Of this family, the hill fox (Vulpes vulpes montana) is the most widespread and common in many habitats. But fox pelts also command a good price and it is not ignored by the ubiquitous poacher.

status uncertain and little information concerning it is available. Of this family, the hill fox (Vulpes vulpes montana) is the most widespread and common in many habitats. But fox pelts also command a good price and it is not ignored by the ubiquitous poacher.

Several members of the cat family may be included in the Himalayan fauna in that their ranges, including those of the tiger and leopard. extend deep into the Himalaya and at high altitudes. Of the lesser cats, some like the jungle cat are recognized as having a separate Himalayan race. However, there are two, other than the snow leopard, which are specificallymountain species—the lynx (Delis lynx isabellina), and Pallas’s cat (Delis manful). The latter is a Central-Asian species and though found in Ladakh, is rare and apparently restricted to the lower Indus valley there. The lynx, which occurs in the upper  Indus valley, Gilgit, Ladakh and The mona or Impeyan pheasant is the national bird el Nepal, where it is also known as the danphe (bird nine colors). Tibet, is a race of the lynx of northern Europe and Asia. Similarly rare, both Pallas’s cat and the lynx are threatened by trapping and shooting. Smaller Species: Besides these larger animals, there is a diversity of smaller species—hares, mouse hares, bats, weasels, martens and more– with varying degrees of rarity, range and reports. It is impossible to describe all here, but mention . must be made of the two races of marmot, the Himalayan marmot (Marmota bohak), and the long-tailed marmot (Marmot caudate), both endearing and common creatures of the higher Himalaya. The red panda, a small animal which i extends east from the Nepal Himalaya, is another well-known lesser mammal of the range. Colorful and cute, it is largely arboreal and nocturnal so is seldom seen in the wild.

Indus valley, Gilgit, Ladakh and The mona or Impeyan pheasant is the national bird el Nepal, where it is also known as the danphe (bird nine colors). Tibet, is a race of the lynx of northern Europe and Asia. Similarly rare, both Pallas’s cat and the lynx are threatened by trapping and shooting. Smaller Species: Besides these larger animals, there is a diversity of smaller species—hares, mouse hares, bats, weasels, martens and more– with varying degrees of rarity, range and reports. It is impossible to describe all here, but mention . must be made of the two races of marmot, the Himalayan marmot (Marmota bohak), and the long-tailed marmot (Marmot caudate), both endearing and common creatures of the higher Himalaya. The red panda, a small animal which i extends east from the Nepal Himalaya, is another well-known lesser mammal of the range. Colorful and cute, it is largely arboreal and nocturnal so is seldom seen in the wild.

Birds: The avifauna of the Himalaya similarly present a fascinating and varied range of species, mainly a conglomerate of palaearctic and Indo- Chinese elements, the former predominating in the western section and the latter richly represented in the eastern areas. Several bird families are endemic to the Himalaya including broadbiils, honeyguides, fmfoots and parrotbiils.  The chir pheasant and mountain quail are endemic and some 14 other palaearctic species including the Himalayan pied woodpecker, blackthroated jay and beautiful nuthatch, are considered by Ripley to give strong evidence of relict forms.

The chir pheasant and mountain quail are endemic and some 14 other palaearctic species including the Himalayan pied woodpecker, blackthroated jay and beautiful nuthatch, are considered by Ripley to give strong evidence of relict forms.

Innumerable and diverse, the colorful species of birds that colonize the Himalayan region defy precising and the several volumes covering various regions should be consulted by interested visitors. Yet some species must be mentioned. The Himalayan pheasants include such spectacular and gloriously plumed members as the resplendent crimson tragopan and the  monal k with its glistening rainbow plumage. The blood pheasant, so called for the blotches of crimson that streak its feathers, is distributed only in the eastern Himalaya and graphically exemplifies the Chinese influence in the avifauna there. Most common and abundant is the generally loweraltitude kaleej pheasant, of which five or six races are recognized. The dapper, gray, black and chestnut koklas pheasant is found more or less on the entire length of the Himalayan system. The eared pheasant and peacock pheasant should perhaps be mentioned amongst the Himalayan phasianidae, though their distribution only touches on the far northeastern section. Others in this family are the partridges and snow cocks, the Himalayan snow cock and the Tibetan snow cock.

monal k with its glistening rainbow plumage. The blood pheasant, so called for the blotches of crimson that streak its feathers, is distributed only in the eastern Himalaya and graphically exemplifies the Chinese influence in the avifauna there. Most common and abundant is the generally loweraltitude kaleej pheasant, of which five or six races are recognized. The dapper, gray, black and chestnut koklas pheasant is found more or less on the entire length of the Himalayan system. The eared pheasant and peacock pheasant should perhaps be mentioned amongst the Himalayan phasianidae, though their distribution only touches on the far northeastern section. Others in this family are the partridges and snow cocks, the Himalayan snow cock and the Tibetan snow cock.

If for no other reason than their impressive size, two birds of prey of this region draw a mention. The golden eagle, a powerful hunter, 31/2 feet (one meter) from beak to tail, is capable even of taking large mammals such as musk deer fawns and the newborn young of mountain sheep; the Iammergeier or bearded vulture is best known for its habit of dropping bones from a height to splinter them on the rocks below, thus releasing the marrow and creating bone fragments on which it feeds.

Migration: The Himalaya are important in the context of Indian bird migration. Of the 2100- odd species and subspecies of birds that comprise the subcontinent’s avifauna, nearly 300 are winter visitors from the palaearctic region north of the Himalayan barrier. One of the most endangered migratory birds of the subcontinent, which nests around the high-altitude lakes of East ern Ladakh, is the blacknecked crane. Hardly half a dozen pairs are known to breed there, though recently its extremely low known world population figure was increased by the discovery of a colony in China. Many of the geese and to be seen in the north Indian wetlands in winter return to these high-altitude lakes for nesting between May and October. Apart from the host of long-distance trans-Himalaya migrants and those that descend to lower levels and the northern plains in winter, there are also species which partake of local seasonal migration within the Himalaya itself. One delightful though not too common example is the crimson-winged wall creeper, fascinating with its distinctly butterfly-like flight.

ern Ladakh, is the blacknecked crane. Hardly half a dozen pairs are known to breed there, though recently its extremely low known world population figure was increased by the discovery of a colony in China. Many of the geese and to be seen in the north Indian wetlands in winter return to these high-altitude lakes for nesting between May and October. Apart from the host of long-distance trans-Himalaya migrants and those that descend to lower levels and the northern plains in winter, there are also species which partake of local seasonal migration within the Himalaya itself. One delightful though not too common example is the crimson-winged wall creeper, fascinating with its distinctly butterfly-like flight.

Until recently it was thought that the mountains formed an insuperable barrier so that migrating birds had to take circuitous routes following the courses of river valleys. However in 1981 it was established by Salim Ali, doyen of Indian ornithologists, that even small birds of starling size are able to withstand the cold and rarefied atmospheres at heights of 20,000-22,000 feet (6000 6700 meters) and some of the larger ducks, geese, eagles etc. have been observed at heights calculated to be even greater than this. Forests: The below-tree line areas of the western region hold forests with close resemblances to European elements and have a greater representation of conifers. Among them the aptly named deodar, tree of the gods, must rank as the most magnificent. Its massive height and girth make it much prized for its timber uses and some of the finest stands have fallen to the axe. The colorful flowering of rhododendrons in their masses is an unforgettable Himalayan experience. The deep crimsons, reds, pinks and creamy yellows of the blooms have no better setting than their natural environment and backdrop of snowy peaks. The majority of the 80 varieties are found in the eastern Himalaya which is also very rich in orchids, presenting a profusion of delicate shapes and colors. This eastern zone is at a lower altitude and has higher precipitation with a higher snow line, thus adding to its distinctive !botanical identity.