Review Overview

2

Summary : 15 different cities are said to have risen and fallen in and around Delhi since the 11th century.

15 different cities are said to have risen and fallen in and around Delhi since the 11th century. The first four ‘Dillis’ were Rajput structures, erected in the southern hills near the present situation of the Qutb Minar. The first historically recorded citadel was Lal Kot, built by the Tomar Rajputs (founders of 8th-century Dillika) in AD 1060. Taken by the Chauhan Rajputs in the 12th century, it was enlarged and renamed Qila Rai Pithora. Then came the Turk slave-king Qutb-ud-Din Aibak, the first Sultan of Delhi (1206), who built India’s first mosque (Quwwat-ud-Islam) and her symbolic tower of victory, Qutb Minar. Under the Khilji dynasty, Islam’s influence spread and the prosperous city of Sari sprang up (Delhi II, 1290-1320) near to present-day Hauz Khas. Next came the Tughlaqs, a bulldog breed who built no fewer than three new cities here in the 14th century—first Tughlagabad , a massive 13-gate fort 10 km (6.3 miles) south-east of Qutb Minar (used for only five years), then Jahanapanah (rapidly abandoned by the mad Sultan Mohammed, who marched the whole population off to distant Daulatabad, near Aurangabad and then marched them all back again 17 years later), and finally Ferozabad (creation of Mohammed’s more stable successor, Feroz Shah), in its day the richest city in the world. This fifth version of Delhi marked the critical move north to the river settlement along the river Yamuna. It lasted a remarkably long time (Delhi’s turbulent history considered), the Tughlaq’s successors (Sayyids and Lodhis) being too busy building tombs to construct new cities.

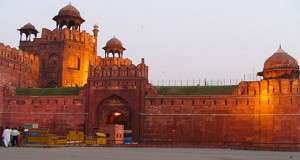

Emperor Sher Shah, the Afghan usurper, displaced the Mughals just long enough to build a sixth Delhi, Shergarh, before they won it back again (1555). But it wasn’t for another century that the seat of Mughal power transferred back to Delhi from Agra. The move took place under Emperor Shah Jahan, who built Shahjahanabad (the present Old Delhi) between 1638 and 1648, obliterating most of old Ferozabad and Shergarh to provide building materials. His son, Aurangzeb, made some improvements to the new capital, but the succession of weak Mughal rulers who came afterwards only paved the way for the infamous invasion of Nadir Shah (1739) when 30 000 Delhi inhabitants lost their lives overnight. After this, the Mughal emperor could only sit sadly in his sacked Red Fort (La Qila) and utter the epitaph of his conquered dynasty: ‘My kingdom extends no further than these four walls.’ Delhi then fell to the British, returning only briefly to Mughal rule during the Indian Mutiny.

The last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah, was reluctantly persuaded out of retirement for this, and suffered for his decision by being marched off into exile in Rangoon. It was the end of the great Mughal Empire in India. Under British rule, Delhi remained in the backwaters until 1911, when The King- Emperor announced the creation of a new city, New Delhi and the transfer of the government from Calcutta, and became a capital once more. To mark its new status as a brand-new city, the eighth (New) Delhi was constructed. The creation of two British architects—Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker—it was designed in magnificent style to reflect the might of the British Empire in India and to accommodate 70 000 people.

The new, modern city sprang up from out of a bare wilderness previously inhabited only by wild animals—a mirage of planned gardens, noble monuments and enormous avenues. Completed in 1931, on the very eve of Independence, it is today considered either the blindest folly of the British Raj or (being generous) its finest gift to modern, free India. Today, New Delhi remains distinctly British. The old imperiousness of the Viceroys has become the political elitism of the Indian ruling-class, and many of the parliamentary, legislative and educational procedures of the Raj remain not only intact, but reinforced by the Indian love of red tape. In Connaught Place, while young gumchewing Delhiites queue with foreign tourists in fast-food Wimpy bars, politicians and place-hunters jostle with filmstars and media types in swanky upmarket hotels and restaurants, and at private dinners. It’s not difficult to detect the ghost of the Raj. Delhi elicits strong likes and dislikes amongst foreign travellers.

On the plus side, it’s an easy introduction to India, with some of the best hotels, restaurants and facilities in the country, and it’s a very convenient base for sightseeing: from here you can jump off to Rajasthan, Varanasi, Kashmir (if the political situation allows) and the ever-popular Golden Triangle. But many find it lacking in colour, character and expression—a city without a face, not like real India at all. In an important sense, what started out being considered the Raj’s greatest contribution to free India—the splendid new city of Delhi—could well become a long-term hindrance, a continuous reminder of a past best forgotten.